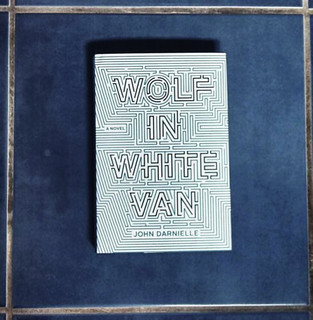

I’ll be honest. Wolf in White Van has been, since its announcement, a book I was determined to like. That’s not necessarily the same thing as a book I know I’m going to like (though I wouldn’t shy away from saying that either), but I pre-ordered it the moment I could, I was already rehearsing how I’d recommend it to friends three months ago, and I knew I’d want to write a review of it. I didn’t want it to be a bad review, so I was determined to like it.

See, though Wolf in White Van is John Darnielle’s debut in novel-writing, it is not his debut in storytelling. Since the early 90s he has been the creative core of indie folk rock band* the Mountain Goats, penning more than 500 songs and said to be (on the sleeve of the novel itself) “one of the best lyricists of his generation.” Emma Stanford says here that in the Mountain Goats lyrics lies Darnielle’s gift for “injecting universal feelings into specific and alien narrative contexts.” We see in Wolf in White Van that same gift in prose. From its backwards beginning, this book is the home of small, epiphanic moments suspending the joy and terror of living. The paint peels, but it’s comfortable; And it’s unsettlingly familiar.

Sean Phillips, designer of postal role-playing game Trace Italian, is to many the sum of his facial disfigurement, patched back together following trauma at age 17. To the reader, he is patched together in a different way: In trips to the liquor store, in his grandmother’s television, in the buildings behind a California arcade.

We know something happened to Sean, and the information seeps out piece by piece, until suddenly we have possession of many of the facts without having been aware of absorbing them. But there are other somethings that happen, too. Sean speaks of side-quests in video games, the subplots you quietly fail before you “just go back into the normal world of the game and continue on toward your objective.” He says he is stuck in a side-quest, and through the clever weaving of two separate traumas and a narrative rooted in memory, Darnielle ensures that it is difficult to recover - or discover - a sense of primary gameplay. In delving backwards through Sean’s life to reach the pinnacle in the murkiest recesses, we find ourselves suspended and lost. There is no present, no quest, only Sean’s life as it is. Not yet finished.

On the insleeve of Wolf in White Van you notice it described as ‘unexpectedly moving’. True, in that it is moving in slightly alien way; it is a unexpected method of moving in that most ‘moving’ stories relate life after trauma as one long traumatic event in itself. Darnielle is more in the business of slotting everyday pegs back into their everyday holes which are now tinged with the aftershocks of a trauma. Going to the liquor store isn’t traumatic, but how can the trivial be reconciled with the life of a man with a face ‘like that’?

There is an eerie sense of fulfilled unfulfillment, a weakly resigned “I don’t know’ to answer your question “If I play it backwards will I find the meaning I’m looking for?”, a raised eyebrow asking you as you dig what it was that told you there was buried treasure to find in the first place. For a book which at times feels like an empty promise, Wolf in White Van left me with something indefinably more. Darnielle crafts his world as Sean crafts the world of Trace Italian: Go in with no expectations of reaching your ultimate goal, but go in all the same.

*This is the genre in which Wikipedia counts the Mountain Goats. I’m going with that because I couldn’t come up with one myself.

This review was written by Kat Sinclair, find her on Twitter -

@katmsinclair